How Much Is Your Diagnosis Worth?

Risk Factor Inflation and Paradox of Shared Savings

This is the 4th newsletter as part of my foundational series on Value-Based Care. If you have not read the first three articles and don't have a background in VBC, I strongly encourage you to read the linked articles below first:

From Doctors to Social Workers (Population Health)

Who’s your PCP (Patient Attribution in VBC)

To quote from my second article - Value-Based Care: The Illusion of Improvement:

Value-based contracts are also called risk-based contracts. At the most basic level, there are two components to this style of contract:

Fixed budget to deliver care to a population (aka attributed lives).

Performance on quality metrics based on targets set by the contract.

In this article, we will discuss how this "fixed budget" is calculated, the financialization of Risk Adjustment, and its impact on PCPs.

The video version of this article is embedded below and on my YouTube Channel.

Audio podcast and Video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Budgets in Healthcare

Why do we need a budget? Healthcare resources, including money, are limited. The government (for Medicare or Medicaid) and private insurance companies need a way to predict how much money they will spend to care for the insured.

When determining this budget, health plans look at two factors:

Demographic factors: These include age, gender, zip code, Medicaid status, living in a long-term institution, dialysis, and disability status (e.g., paraplegia, hemiplegia)

How sick is the patient? This is based on the diagnosis codes submitted by providers when they bill for patient care. For example, a person with CHF and COPD will cost more than someone with CHF alone.

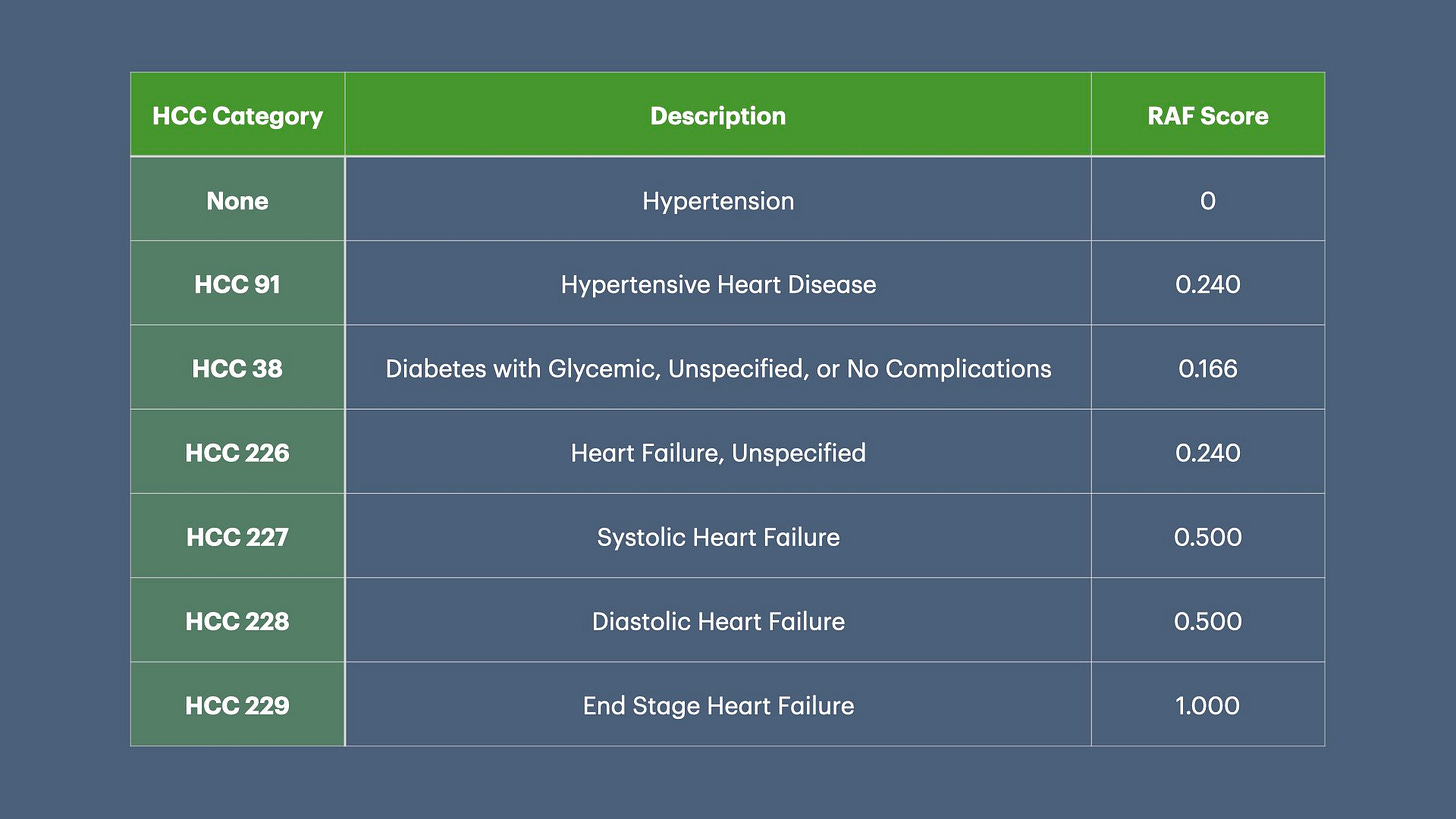

However, the ICD-10 set contains approximately 72,000 diagnosis codes. Conducting actuarial analysis for each individual code can get very complicated. Enter Hierarchical Coding Conditions (HCC).

Hierarchical Coding Conditions (HCC)

The initial draft of the CMS-HCC risk adjustment payment model was released on March 29, 2002, and the final version was announced on March 28, 2003 (pdf link). Implementation began in January 2004.

HCCs categorize diagnoses into related groups based on clinical complexity and expected future healthcare costs. To keep the discussion and calculations simple, I will ignore the role of demographic factors and only use HCC in the cost calculations below.

(The following calculations are a “back of the napkin” calculation. The actual calculations are a lot more complicated.)

These costs are calculated as follows:

We know that the average healthcare cost per person in 2022 was $13,493. Now we can calculate that a person with diabetes, i.e., HCC 38 with RAF score = 0.166, will cost the insurance company $2,239.83 in 2023 (ignoring demographic factors):

(This number is very low as we did not add the expected cost due to demographic factors).

Using the formula above, let’s take the example of 3 hypothetical patients, Joe, Sally, and James, with multiple medical conditions and calculate their expected costs:

As you can see from the table above, capturing all the medical conditions is crucial, as it makes a big difference in the budget. Even if an organization is able to reduce the cost of care, it will not achieve any shared savings if its budget is low.

For people interested in a more detailed analysis of how budgets are calculated in VBC contracts, this article by Milliman is a great start: Risk Adjustment and Shared Savings Agreements (pdf).

Different RAF Models

In addition to the CMS-HCC model, several other models are used by different health plans. Below is a brief description of them.

ACG (Adjusted Clinical Groups) System: Developed by Johns Hopkins University, this model is used by some commercial payers and Medicaid programs.

DxCG Intelligence: Developed by Verisk Health. It uses proprietary algorithms to predict future healthcare costs. Incorporates pharmacy data in addition to medical claims. It also offers different versions for different populations (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial).

CDPS (Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System): Primarily used in Medicaid populations.

CRG (Clinical Risk Groups): Developed by 3M. Used by some state Medicaid programs and commercial insurers

Insurance companies may use different models depending on the specific population and program requirements. This means that in a PCP panel, different metrics may be used to assign a budget for different patients.

Impact of RAF on VBC Budget

The impact of RAF on the VBC budget cannot be underestimated. There are only 2 ways to "reduce" the cost of care:

Decrease the total cost of care (TCOC) by:

Decreasing utilization,

Use lower cost services, or

Decrease prices paid for services.

Capture all medical diagnoses, which increases the future budget.

Since it is very hard to reduce the total cost of care, most organizations (health plans and ACOs) predominantly focus on "appropriate risk adjustment." Essentially, this involves finding and documenting any diagnosis that will increase the risk score and, therefore, the budget.

Diagnoses Inflation—The Art Of Making People Look Sicker

Since diagnosis codes (ICD-10) codes form the basis of budget, the focus of most organizations in VBC contracts is making sure that the ICD-10 codes are "accurate." However, there is a fine line between "accurate coding" and "upcoding." This falls into 2 categories:

Coding non-existent diagnosis

This varies from fraudulent (e.g., making up a diagnosis in the medical chart to increase the RAF score) to biased clinical decision-making in favor of a higher risk score.

For example, Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation are two separate HCC categories that increase the risk score. These 2 diagnoses can be independent of each other, but clinically, you make the argument that long-standing hypertension may lead to Atrial Fibrillation. Providers in VBC incentivized to increase risk scores may make a biased clinical judgment and add "Hypertensive Heart Disease" as a 3rd diagnosis, increasing the risk score by 0.240.

Another example (which CMS recently closed the loophole) was in people diagnosed with depression. Under the older V24 model, “Depression, NOS” (Not otherwise specified) did not have an HCC value, but “Major Depression” has an HCC score of 0.405.

Every single slide set across all ACOs that I have seen encouraged providers to use the ICD-10 for "Major Depression" instead of "Depression, NOS," which increased the budget in 2023 by approximately $5,465.88 ($13,496 x 0.405) per patient.

Exploiting Thresholds to Inflate Disease Diagnoses

As people age, their lab values change, sometimes falling below cut-off thresholds for disease classification, even when clinically insignificant. This issue is being exploited under VBC to label patients with diseases that are either non-existent or unlikely to cause future problems." Let’s look at a couple of examples below:

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is diagnosed using the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) test, with a cutoff value set at 0.8. Clinically, PAD typically manifests as leg pain during walking. However, if a person has an ABI of 0.79 but experiences no leg pain while walking—or cannot walk due to arthritis, which limits their ability to elicit symptoms—can we truly consider this person to have clinically significant PAD?

Many health plans send providers to patients’ homes to perform ABI and exploit the ABI threshold to document that they have PAD.

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Stage 3 is diagnosed when the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is below 60. GFR is calculated using a blood test called Creatinine. It is important to note that GFR often decreases with age (although some literature suggests that GFR does not necessarily decline as people get older). However, since Creatinine measurement is not an accurate measure of GFR, if an 80-year-old individual has a GFR of 59, do they truly have clinically significant CKD Stage 3?

Now that we understand the common techniques for risk adjustment, let us make James look sicker in the table below.

By changing and adding new diagnoses, we have increased the budget by almost $18,000, and James is not one iota sicker.

(Some of the loopholes in the slide above were closed by CMS when they recently transitioned from the HCC V24 model to the V28 model.)

Impact Of Upcoding On Patients

VBC contracts have mainly focused on people with Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, i.e., people who have retired. However, more and more VBC contracts are being used in commercial populations, which will impact disability and life insurance policies.

One unintended consequence of Risk Adjustment and "appropriate coding" is that people will be diagnosed with more medical problems. I am not an actuary, but my understanding is that adding these "risk diagnoses" will increase the premium as these people will be considered higher risk.

Therefore, the financialization of Risk Adjustment creates a monetary windfall not only for health plans but also for any company involved in disability and life insurance.

Risk factor inflation

Over the last several years, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have used the uncertainty of diagnosis and deference to clinical decision-making to game risk adjustment.

All MA plans have hired an army of providers and heavily incentivized them to find medical diagnoses to drive up risk adjustment. Most of these providers are Nurse Practitioners (NPs), and since they can practice independently in most states, they are sent to patients’ homes to evaluate and document all medical conditions. They are also trained to perform ABI and diagnose Peripheral Artery Disease (our example above). This Risk Factor Inflation has led MA plans to pocket up to $50 billion from Medicare for diseases not under treatment.1

While I cannot find good data on the gamification of risk adjustment in provider-led ACOs, after talking to several providers nationwide, I know that this is happening. Providers are being heavily incentivized & penalized in all ACOs to document all medical conditions “properly.” Aledade, a provider-led ACO, had a whistleblower lawsuit2 against them for Medicare fraud due to risk adjustment (the lawsuit was subsequently dismissed).

When accounting for risk factor inflation and ACO benchmarking3, most savings touted by value-based programs turn out to be illusory.4

The question then becomes, why are we subjecting PCPs to this clerical exercise? Because it allows health plans to blame providers for rising healthcare costs.

Impact on PCPs

More clerical work and Decreased Time for Patient Care

Since PCPs are responsible for the “whole health” of the individual, insurance companies have determined that they are responsible for “appropriate risk-adjusted” coding - even if several conditions are being managed by specialists. For example, if a cardiologist is managing heart failure, it is the PCPs responsibility to ensure that the proper risk-adjusted heart failure diagnosis is billed by PCP. This risk-adjusted coding decreases the time it takes to care for patients as providers spend more time completing medical documentation.

Several insurance companies, in partnership with “Risk Adjustment Companies,” force PCPs to document not just in the EHR but also in another system used for risk adjustment controlled by the insurance company (some even pay a small fee for double documentation). This again reduces the total time available to care for patients.

Deteriorating Relations with Patients

When insurers send providers to patients' homes for risk adjustment visits, they often find diagnoses that are not clinically relevant. Patients are then asked to talk to their PCP to address their “medical issues.” As you can imagine, patients get upset as they feel their PCP missed their diagnosis (even though it may have been discussed in the past and people forget). This leads to patients getting angry with PCPs and creates unpleasant situations in the office, sometimes resulting in the loss of permanent trust.

Financial Impact on Private Practices

As healthcare gets more expensive year over year, insurance companies are decreasing payments to providers, including PCPs. Most providers have taken huge pay cuts in the last 10 years, especially when accounting for inflation. This impacts private practices, as the cost of running the practice has skyrocketed while reimbursements have declined.

Under VBC contracts, PCPs are forced to take financial risks for the total cost of care of their patient panel. If the cost of care exceeds the budget, then PCPs must pay the insurance company back. Since small PCP practices cannot control socioeconomic & environmental health determinants and don’t have money to pay back insurance companies, they are forced to join an ACO (if they have access to one) to retain independence, merge with larger practices, or sell out.

If the cost of care increases beyond the budget, then PCPs must pay the insurance company back.

Regulatory Tightrope: Caught between a Rock and a Hard Place

In the last several years, CMS and other regulatory agencies have been cracking down on risk adjustment. Since Medicare Advantage companies have been at the forefront of gaming risk adjustment, the focus of regulatory agencies is on MA plans. 5

However, this puts providers in a pickle. Insurance companies set incentives and aggressively penalize providers for ensuring patients are risk-adjusted properly. Since providers are responsible for ensuring accurate diagnoses, the insurers wash their hands off during an audit. The choices providers face include:

Not listening to insurance companies and going bankrupt.

Code aggressively for risk adjustment but then risk being subjected to regulatory oversight with the possibility of being prosecuted for fraud.

Essentially, VBC has financialized the healthcare system and offloaded the regulatory risk to front-line doctors.

Up Next

Now that we understand how risk adjustment has wreaked havoc on PCPs, we will discuss why quality metrics don’t improve care that is delivered to people, but increase the burden of data collection and submission on PCPs.

However, before we turn our attention to quality metrics, I am going to complete the VBC series by discussing bundled payments in the next newsletter.

If you liked this article, please consider sharing it.

You can unlock access to the paid membership tier for free using the link below to share this article via email, text message, or social media. Learn more about these perks and track your progress on the leaderboard.

Mollica, C. W., Tom McGinty, Anna Wilde Mathews and Mark Maremont |. Graphics by Andrew. (2024, July 8). Exclusive | Insurers Pocketed $50 Billion From Medicare for Diseases No Doctor Treated. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/health/healthcare/medicare-health-insurance-diagnosis-payments-b4d99a5d

Schulte, F., & News, K. H. (2024, March 6). Aledade accused of Medicare fraud by whistleblower. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/ai-and-machine-learning/whistleblower-accuses-aledade-largest-us-independent-primary-care-network

Benchmarking is a whole article in itself. For a primary see the article “A Playbook of Voluntary Best Practices for VBC Payment Arrangements” (pdf link)

McWilliams, J. M., & Chen, A. J. (n.d.). Understanding The Latest ACO “Savings”: Curb Your Enthusiasm And Sharpen Your Pencils—Part 1. Health Affairs Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20201106.719550

DOJ and OIG ramp up enforcement of risk adjustment coding: 5 compliance tips for providers. (n.d.). Retrieved September 25, 2024, from https://www.thompsoncoburn.com/insights/blogs/health-law-checkup/post/2022-01-27/doj-and-oig-ramp-up-enforcement-of-risk-adjustment-coding-5-compliance-tips-for-providers

Rising Regulatory Scrutiny of RAF Scores | FTI Consulting. (n.d.). Retrieved September 24, 2024, from https://www.fticonsulting.com/insights/articles/rising-regulatory-scrutiny-raf-scores

I'm pleased to have found your 'stack, Doctor.

"While I cannot find good data on the gamification of risk adjustment in provider-led ACOs, after talking to several providers nationwide, I know that this is happening."

I'll just observe that you've placed your finger directly on the pulse of the matter. What you're describing is extremely common across all dimensions of goods and services paid for by underwritten indemnification. There is a direct corollary in automotive collision repair and automotive warranty repair.

There will always be a hierarchy of diagnostic severity, based on causality. There are always incentives for overstatement and understatement, according to loss ratios and actuarial assessments.

The "Holy Grail" is always that most elusive of standards; objective performance criteria. Administrative bloat is the inevitable outcome of cost control initiatives, which fuels vertical integration and leads to moral hazard stemming from conflicts of interest.

Thank you for your fascinating expose of the coding and claiming structure. Please continue; the work is important to understanding how to strike a balance between loss ratio control and good faith indemnification.

It's way worse than you think. 53% of you premiums are returned to you as benefits by your health insurance company. 84% of health spending in the US is on avoidable chronic disease. If we automate the entire insurance process, and I can show you how, we can get back that wasted 47%. If we can educate people and put teeth in reading and following that education, and I can show you how, then we can get the US down to OECD levels of avoidable chronic disease. I can also show you how to do this. That song will chop another 25% from the cost of healthcare. Let's call that 60+% total savings.

I suspect that you will not listen, nobody does, but this problem has been solved, by us. Read my articles.