What is a Disease?

At the intersection of doubts, decisions, and dollars

In my first article, “From Doctors to Social Workers,” I discussed the concept of “Health” as defined by WHO. To recap the definition of Health:

A state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

While defining Health is challenging, defining “what a disease is” is even harder. This article attempts to define “disease” and explain how these definitions impact society.

The video version of this article is embedded below and on my YouTube Channel.

Audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

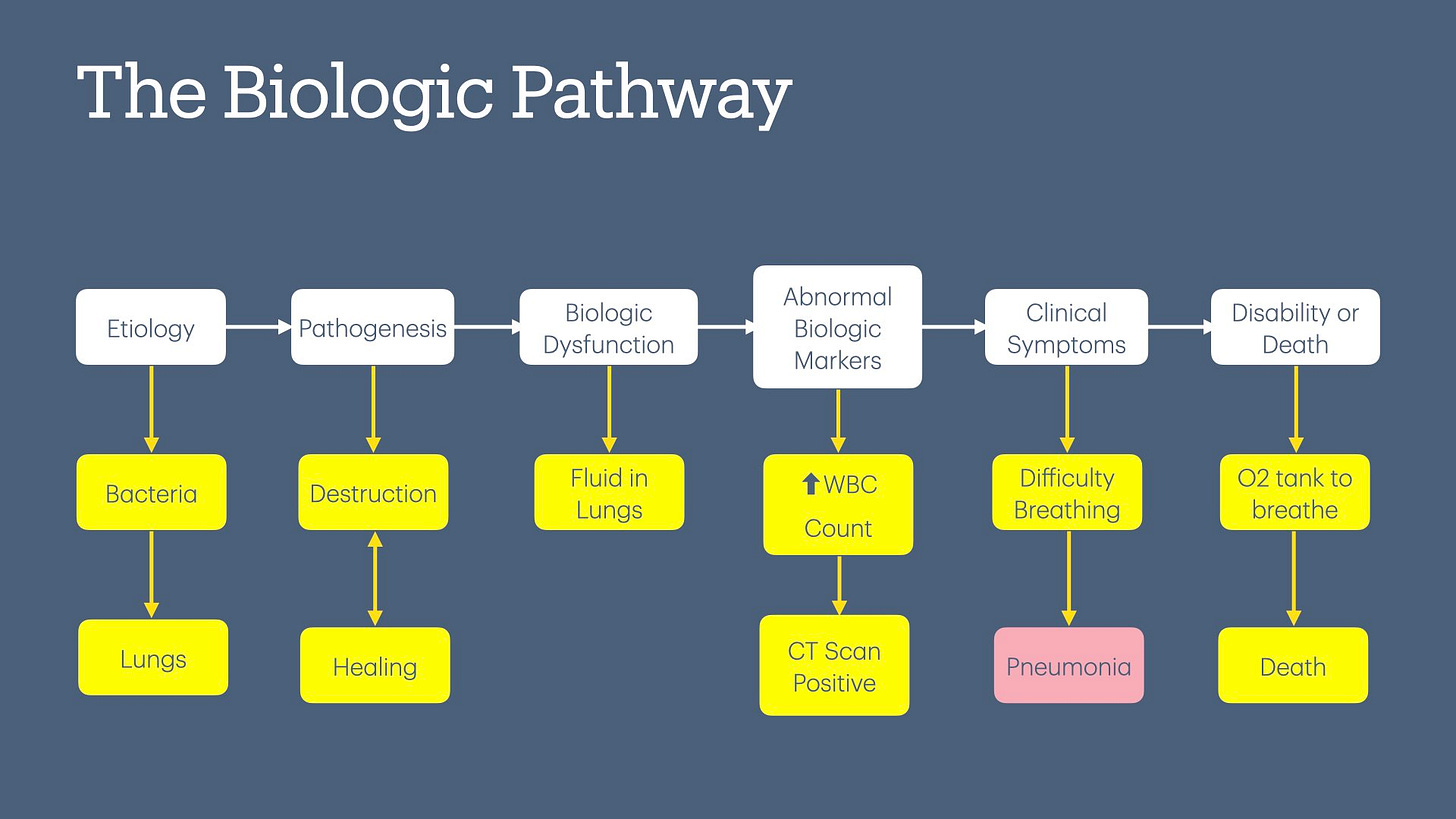

The Biologic Pathway

The academic literature has used several frameworks to define “Disease,” but I will focus on the medical or biologic framework. This is a high-level overview, and people without a medical degree should be able to follow easily.

Below is a breakdown of key steps.

Etiology

The etiology of a disease is the study of the factors that cause it. These factors can be a single cause, such as bacteria, which can cause pneumonia, or more complex causes, such as a combination of multiple environmental and socioeconomic risk factors, which cause heart disease.

Pathogenesis

In this stage, the body's biological processes behave abnormally. E.g., bacteria that enter the lungs start destroying lung tissue but the person does not have any symptoms. I am calling this “bacterial invasion & lung destruction” and not pneumonia on purpose, as the body may be able to fight off the bacteria and repair the lung tissue on its own.

Biological Dysfunction

In this stage, the body cannot control the abnormal pathogenesis, resulting in biologic dysfunction. E.g., Lungs fill up with infiltrate, aka, fluid, as the rate of lung destruction is faster than the body can repair.

Abnormal Biologic Markers

In this stage, certain lab or imaging markers may start showing evidence of biologic dysfunction prior to symptom onset. E.g., WBC count in labs may increase as more WBCs are required to fight the bacteria invading the lung. A CT Scan of the lung may show the presence of infiltrate. Other examples include high blood pressure and high blood sugar in a person without any symptoms.

Clinical Symptoms

This stage is where biologic dysfunction or damage starts manifesting symptoms. E.g., Fever and difficulty breathing. Today, clinical symptoms form the basis of most pneumonia diagnoses, hence its definition.

Disability of Death

In the last stage, the person develops temporary or permanent damage to the body from the disease, or the disease leads to death. E.g., Oxygen tank is required to help with breathing due to permanent damage from pneumonia.

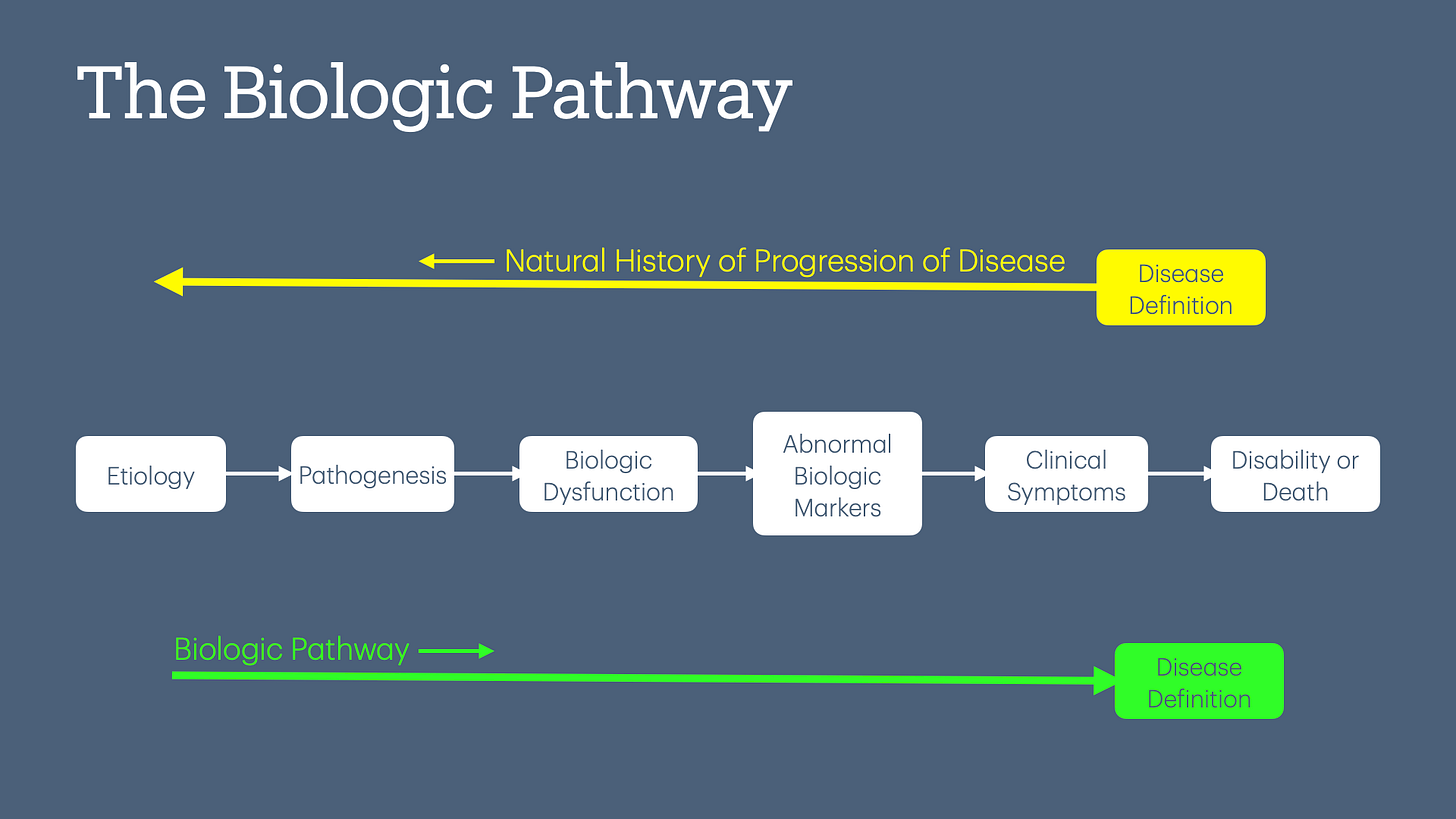

Some of you may recognize what I described above is often called the “natural history of disease.” However, this term assumes that the “disease” is already defined (or at least its major characteristics are known) and works backward to identify the biological pathways. In contrast, my use of the term “biologic pathway” is forward-looking and does not assume that all pathways, including abnormal ones, will necessarily lead to “disease.” This distinction is critical in modern medicine, where biomarkers and advanced imaging can identify “abnormalities” without a clear understanding of their natural progression. Without this information, we often retrofit these findings into existing disease models, a practice that conveniently benefits the current medical establishment.

The biological pathway described above is still a simplification of the complex pathophysiological processes in the human body. Not all processes follow the same sequence or order. However, using the biological pathway as a starting point helps determine where in the process we should define a disease, if at all.

Goals of Defining a Disease

When defining a disease, we have to consider what we are trying to achieve. Some of these goals are:

Facilitating diagnosis and treatment to alleviate active symptoms and prevent disability or death.

Prevent future symptoms, disability, or death.

Prevent a contagious “disease” from spreading.

Facilitate communication by creating a shared language, ensuring consistency in understanding.

Resource allocation.

Research to understand the disease better and develop treatments.

Defining Disease

Considering the above goals, we must decide where in the biologic pathway to define the disease.

When a person has clinical symptoms or develops a disability, an accurate disease definition and description facilitates diagnosis and treatment.

When clinical symptoms don’t exist, defining a disease is an exercise in tradeoffs. The benefits to consider include preventing symptom onset (if ever), disability, or death or, in the case of public health, spreading contagious disease. Common risks include the side effects of treatment, the cost of treatment (both to individuals and society), and lost productivity (to take a pill, doctor appointments, labs, etc).

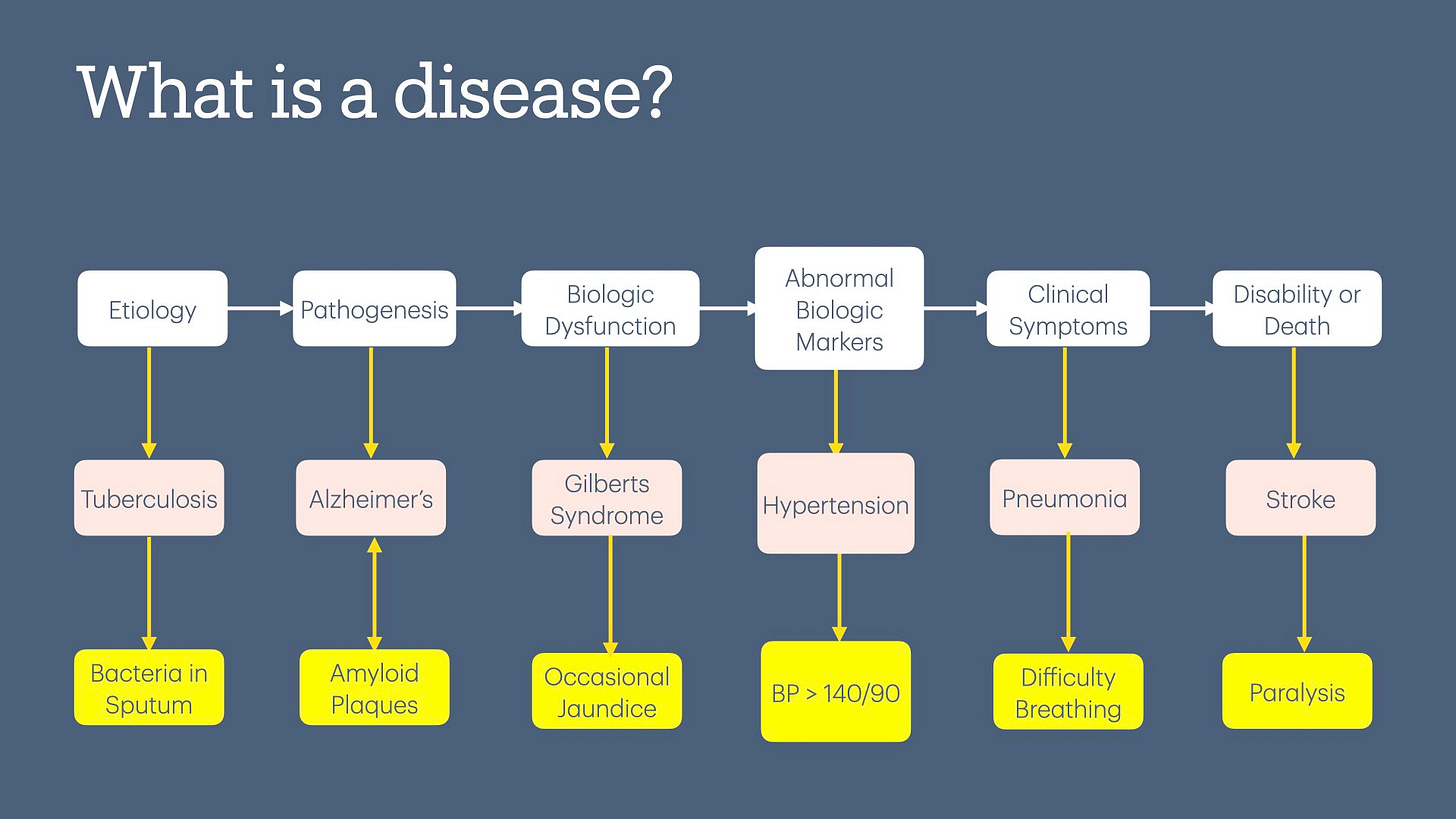

Let’s look at examples of some diseases that have been defined in each stage of the biologic pathway.

Disability

Stroke: Many people receive medical care after a stroke has already occurred, and there is some disability, e.g., paralysis. Aspirin and statins after a stroke decrease the risk of future strokes, while Physical Therapy may restore or improve strength due to paralysis.

Clinical Symptoms

Pneumonia: Antibiotics for fever and difficulty breathing from pneumonia help the body fight the infection and allow the body to heal, resolving symptoms and decreasing the risk of disability.

Abnormal Biologic Markers

Hypertension: BP > 140 / 90 mm Hg

Diabetes: Fasting blood sugar > 126 mg/dl

Lung nodule: Found during lung cancer screening

The goal of defining these biologic markers as diseases is to decrease the risk of future symptoms. However, one could also debate that these are not diseases per se, but risk factors for disease.

Biologic Dysfunction

Gilberts syndrome: reduced ability to remove bilirubin from the body, leading to mild jaundice. Harmless condition but defined as a disease.

Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM): Blood flowing from the heart may be obstructed during intense exercise. Mostly asymptomatic and generally presents with syncope or sudden cardiac death.

Long QT Syndrome: Abnormal ion channel exchange in the heart, either from mutations or acquired (drugs are the most common cause). Mostly asymptomatic and generally presents with syncope or sudden cardiac death.

Pathogenesis

Alzheimer's Disease: the ongoing development of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain, even before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Osteoporosis: In 1994, WHO defined osteoporosis as a disease characterized by gradually weakening bones, initially attributed to aging.

Etiology

Tuberculosis: The presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum, irrespective of evidence of pathogenesis, biological dysfunction, or symptoms. The reason to define tuberculosis based on etiology is because it is contagious and a very high public health risk.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria: Presence of bacteria in urine without any evidence of pathogenesis, biological dysfunction, or symptoms. (Urinary Tract Infection is defined based on bacteria + symptoms).

Asbestosis & Lead Exposure: Exposure to high levels of asbestos or lead regardless of pathogenesis, biologic dysfunction, or symptoms. The goal is to decrease the risk of pathogenesis leading to symptoms.

We can debate that the above examples could be classified under a different biological stage. This highlights the inherent complexity and subjectivity in defining and classifying diseases. The process of defining a disease is not always clear-cut and often involves decisions influenced by scientific, medical, social, and even economic considerations. This ambiguity underscores why disease definitions are frequently debated and why they evolve over time.

What is Normal?

Using the forward-looking term "biologic pathway" instead of the backward-looking "natural progression of disease" makes defining "what is a disease" more challenging. Starting with a biologic process requires confronting the ambiguity and uncertainty of where normality ends, and disease begins. For example:

Grief and Depression

It is very hard to determine where normal grief ends and depression begins. The DSM diagnosis has evolved over the years to more recently include a new disease, “Prolonged Grief Disorder.”1 One can argue that the changes in these definitions were made to:

better differentiate normal and abnormal “grief” patterns,

medicalize “grief” so that pharmaceutical companies can sell antidepressants.

Cancer

When does the presence of a few “dysplastic,” aka cancer cells produced during normal cell turnover (and destroyed by the body), become abnormal, i.e., cause disease?

These two examples show that there is often no clear boundary between normal and disease. Using the backward-looking term “natural history of disease,” particularly for emotionally charged conditions like cancer, creates a bias toward identifying and eradicating every dysplastic cell the body produces, i.e., overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

In contrast, starting with pathophysiology and examining the “forward-looking “biologic pathway” might lead to different questions:

What biologic pathway will these dysplastic cells follow?

Are these dysplastic cells going to cause symptoms, i.e., cancer?

I may be arguing about semantics here, but semantics shape public perception of disease—and healthcare costs.

Evolution of Disease Definitions

Generally, proposals to evolve the definition of a disease fall into the following categories:2

Create New Categories of ‘‘Pre-Disease’’

Pre-disease categories aim to identify individuals at high risk of developing full-blown disease, hoping to enable targeted interventions. These categories are often based on measurable biomarkers or thresholds. For example:

Prehypertension (now Stage 1 Hypertension): BP between 120/80 and 130/903

Prediabetes (Impaired Fasting Glucose): Fasting sugar between 100 and 126

Osteopenia: T-score between 1 and < 2.5

Lowering Diagnostic Thresholds

The definition of both hypertension4 and diabetes has shifted over time, with lower BP and fasting sugar thresholds now used to define the condition. This has led to more people being classified as having hypertension and diabetes.5

The goal of lowering the diagnostic threshold is to prevent or delay future symptoms and disabilities. Interestingly, there is some irony in the concepts of "pre-disease" and a lowered diagnostic threshold—both are intended to reduce the occurrence of future events. This begs the question—what is the real purpose of defining “pre-disease?” This has led to a furious debate in the literature, with many considering prediabetes to be a dubious disease.6

Proposing Earlier Diagnosis or Different Diagnostic Methods

This technique is used to identify diseases early in the biologic pathway to reduce future symptoms or disability. Examples include:

Myocardial Infarction (heart attack): The definition has evolved from being based on symptoms to EKG changes and now to highly sensitive troponin-based biomarkers.7

Rheumatoid Arthritis: The definition has evolved from joint deformity causing disability to the presence of autoantibody biomarkers in blood.

Cancer: The definition has shifted from relying on the presence of symptoms to now encompassing nodules or polyps identified through screening. The “cancer in blood cells” testing attempts to shift screening to an earlier stage in the pathway.

Depression: The definition evolved and broadened the range of symptoms that constitute depression and included grief/bereavement in the definition.

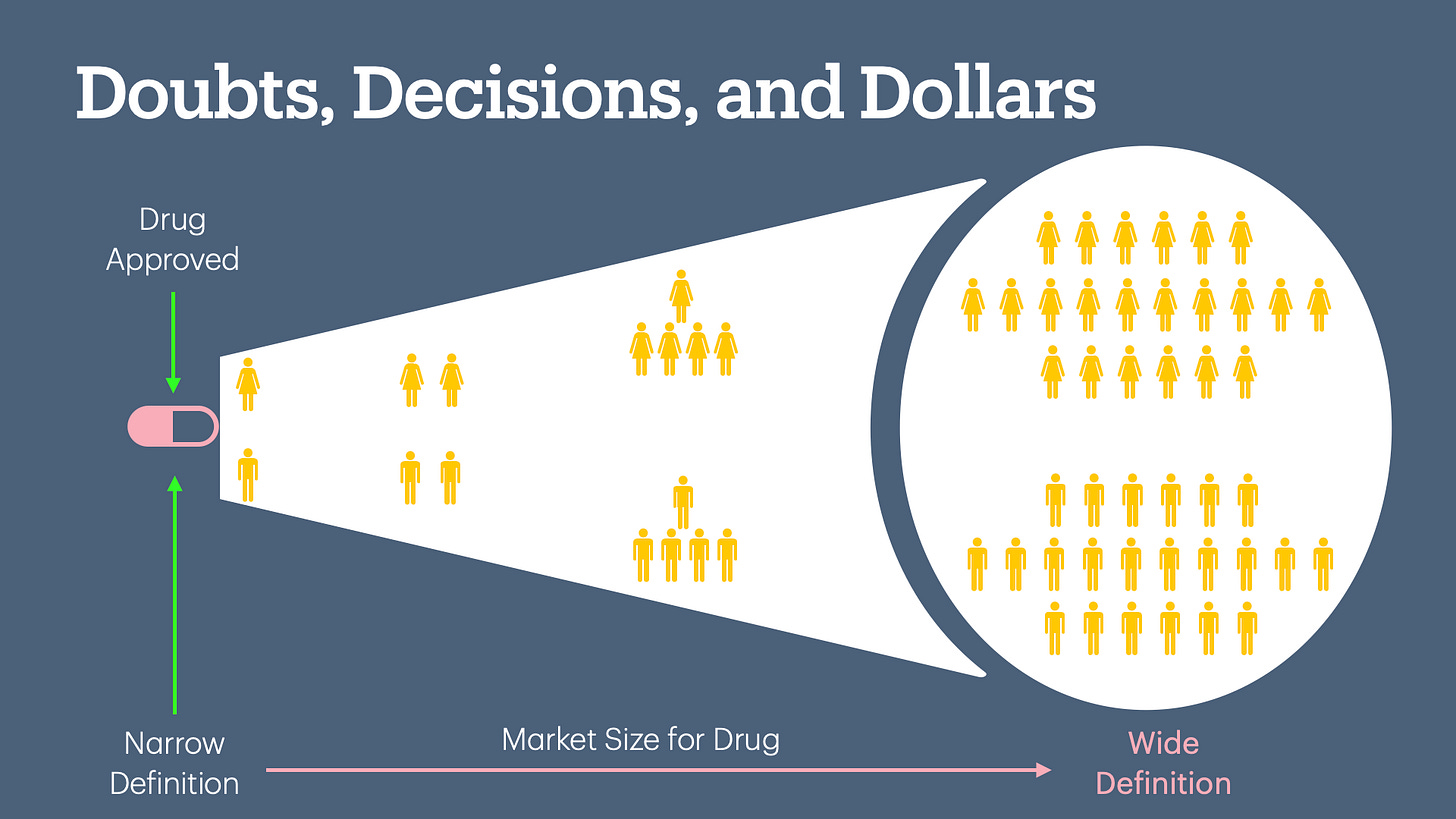

Doubts, Decisions, and Dollars

Given all the scientific uncertainty, the subjective boundaries between normal and abnormal, and the social and economic influences, getting the definition right has significant implications—not only for health outcomes but also for creating new markets to sell medications.

A growing body of evidence shows how the industry influences disease definitions and guideline development to expand its market.8 As new pathophysiological processes are discovered (e.g., troponin for cardiac injury), they are often retrofitted into existing disease models (e.g., using troponin to diagnose Myocardial Infarction). Pharmaceutical companies take advantage of these changes; marketing medications initially approved for diseases defined by different criteria or higher thresholds to a much larger population after redefinition, resulting in overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Given this phenomenon, some have proposed that medical evidence should have an expiration date.9 Medications approved for a disease defined in the later stages of the biologic pathway may not be effective when the disease is redefined to include earlier stages. These medications must be studied again to confirm their effectiveness under the new definition.

For example, the REDUCE-AMI trial recently demonstrated that beta-blockers, the standard of care after a heart attack, may not be effective in the era of coronary stents (especially for people with normal ejection fraction).10 By the way, using beta-blockers after a heart attack remains a quality metric, and this has not changed since the publication of the landmark study.

There is a quote often used in healthcare when discussing healthcare costs:

The most expensive thing in healthcare is the doctor’s pen.

What is less often discussed is the significant role the pharmaceutical industry plays in shaping the conditions under which doctors prescribe medications. By influencing disease definitions, clinical guidelines, and marketing strategies, the industry fosters an environment, including cultural expectations, where prescribing their products becomes the default option. Diseases are complex and often lack clear solutions, particularly when defined earlier in the biological pathway. Doctors who opt for nuanced discussions with their patients and disregard industry-driven guidelines risk medico-legal liability for not adhering to the established recommendations.

The most expensive thing in healthcare is NOT the doctor’s pen—it is the unseen hand of the pharmaceutical industry in concert with large consolidated health systems, creating the illusion of choice when clicking EHR buttons. Yet, because doctors hold the pen or the mouse, the blame for rising healthcare costs falls on them.

Up Next

Now that we understand the complexity of defining a disease, we will discuss the basics of screening for disease in the next article.

If you liked this article, please consider sharing it.

You can unlock access to the paid membership tier for free using the link below to share this article via email, text message, or social media. Learn more about these perks and track your progress on the leaderboard.

Barry, E. (2022, March 18). How Long Should It Take to Grieve? Psychiatry Has Come Up With an Answer. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/health/prolonged-grief-disorder.html

Moynihan, R. N., Cooke, G. P. E., Doust, J. A., Bero, L., Hill, S., & Glasziou, P. P. (2013). Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: A cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Medicine, 10(8), e1001500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500

2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines | Hypertension. (n.d.). Retrieved December 26, 2024, from https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/hyp.0000000000000065

Whelton, P. K. (2019). Evolution of blood pressure clinical practice guidelines: A personal perspective. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 35(5), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2019.02.019

When reading or hearing about a sudden increase in the prevalence of a disease, consider whether the disease's definition has been expanded to include more people under its classification.

Piller, C. (2019). Dubious diagnosis. Science, 363(6431), 1026–1031. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.363.6431.1026

Hajar, R. (2016). Evolution of Myocardial Infarction and its Biomarkers: A Historical Perspective. Heart Views : The Official Journal of the Gulf Heart Association, 17(4), 167–172. https://doi.org/10.4103/1995-705X.201786

Doust, J. A., Treadwell, J., & Bell, K. J. L. (2021). Widening Disease Definitions: What Can Physicians Do? American Family Physician, 103(3), 138–140. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2021/0201/p138.html

Kitsis, E. A. (2011). The Pharmaceutical Industry’s Role in Defining Illness. AMA Journal of Ethics, 13(12), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.12.oped1-1112

Moynihan, R. N., Cooke, G. P. E., Doust, J. A., Bero, L., Hill, S., & Glasziou, P. P. (2013). Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: A cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Medicine, 10(8), e1001500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500

Greene, P., Prasad, V., & Cifu, A. (2019). Should Evidence Come with an Expiration Date? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(7), 1356–1357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05032-4

Trials, C. (2024, July 2). Review of the REDUCE-AMI trial [Substack newsletter]. Cardiology Trial’s Substack.

Yndigegn, T., Lindahl, B., Mars, K., Alfredsson, J., Benatar, J., Brandin, L., Erlinge, D., Hallen, O., Held, C., Hjalmarsson, P., Johansson, P., Karlström, P., Kellerth, T., Marandi, T., Ravn-Fischer, A., Sundström, J., Östlund, O., Hofmann, R., & Jernberg, T. (2024). Beta-Blockers after Myocardial Infarction and Preserved Ejection Fraction. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(15), 1372–1381. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2401479