Solving Obesity with a Quality Measure

How BMI screening quality measure burdens PCPs without decreasing obesity

In this article, we take a deep dive into a quality measure that summarizes everything that is wrong with using them to improve health: “BMI Screening and Follow-Up Plan.” I will show you how this quality measure gives the impression of “taking action,” does not solve the underlying problem, and increases “busywork” for busy front-line physicians.

The video version of this article is embedded below and on my YouTube Channel.

Audio podcast and Video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Before discussing the problems with this quality measure, let's look at the measure itself.

Anatomy of “BMI Screening and Follow-Up Plan” Measure

Quality Measure Description

Percentage of patients aged 18 years and older with a BMI documented during the current encounter or within the previous twelve months AND who had a follow-up plan documented if the most recent BMI was outside of normal parameters.

Denominator

Age ≥ 18

Valid Patient Encounter based on CPT-I Codes within 12 months

(see PDF at the end of the article for list of CPT codes)

Encounter is not via Telehealth (based on modifier or Place of Service Codes)

Numerator

Measure Height and Weight (patient-reported values are not counted).

If BMI ≤ 18.5 or ≥ 25, document a follow-up plan.

Documentation should be on the day of the encounter or within the last 12 months of the encounter date.

Denominator Exclusions

Any patients in this category will not be included in the denominator:

On hospice (HCPCS = G9996)

Pregnancy (HCPCS = G9997)

When these HCPCS codes are used in billing, the patients are excluded from the denominator. More on these HCPCS codes later in the article.

Denominator Exception

This removes people from the denominator if there is an appropriate justification by the physician:

The patient refused to be weighed

Appropriate medical reasons as to why reducing BMI may complicate other conditions such as nutritional deficiency, physical disability, or dementia.

An urgent or emergent medical condition where delay would jeopardize health

The difference between “exclusion” and “exception” is that people in the “exclusion” category will never be in the denominator in the first place. People in the “exception” category will be counted in the denominator unless there is documentation on why they should be excluded.

Reporting Period

Valid patient encounter between Jan 1 and Dec 31.

Data Sources

Billing codes (HCPCS codes - similar to CPT codes used for billing and mainly used by ancillary providers)

Medical chart abstraction

Now that we know the details of this quality measure, let’s analyze its rationale, and if it is achieving its intended outcome.

Rationale for Quality Measure

If I had to sum up the rationale for creating a quality measure for obesity, it would be the following 2 points:

Obesity rates are rising.

We need to ensure that doctors are screening and treating obesity.

While this appears to be a reasonable argument on the surface, it ignores the fact that obesity is the result of complex socioeconomic issues.1 The “follow-up plan” part of the quality measure results in the “medicalization” of obesity without ensuring adequate insurance coverage for treatment, and to distract from the root causes of obesity.

This quality measure was developed to align with the USPSTF Guidelines for BMI screening. However, while the USPSTF guidelines suggest intervention over a BMI of 30, the screening measure decreases this to 25!

Problems with Quality Measure

Prevention vs. Treatment

As discussed before, the development of obesity in societies is due to complex socioeconomic and cultural factors. While screening for obesity is portrayed as “preventive,” true prevention is the prevention of obesity itself. The BMI quality measure deflects attention from root causes and shifts the responsibility and blame to front-line physicians. (I go into a little more detail in my video on this topic).

Fluctuating BMI

Let us take the example of a person whose BMI fluctuates around 25. This person has an Annual Physical in May with their PCP, and the documented BMI is 24.5. In December, the patient was seen for a common cold, and their BMI was documented as 25.5 (it is winter, and the person was wearing a winter jacket and boots). If the PCP does not document a BMI plan, they are considered non-compliant.

Insurance Coverage for Treatment

If a person is obese, there is an opportunity to initiate a treatment plan with varying degrees of efficacy. These treatments include:

Lifestyle/behavioral therapy, including intensive behavioral therapy.

Weight management counseling.

Medications, e.g., Phentermine, naltrexone-bupropion, and the current favorites GLP-1 agonists.

Bariatric surgery.

Insurance coverage for these treatment plans is variable at best and non-existent at worst. If insurance does decide to cover medical treatment, it generally requires documentation (read = prior authorization) of medical necessity.

Quick PCP Rant

Most PCPs typically discuss weight management during an Annual Physical. However, insurance companies rarely cover follow-up visits specifically for obesity management. Getting approval for weight management services like behavioral therapy or dietician visits is unpredictable, forcing clinic staff to repeatedly submit paperwork to insurance companies for prior authorization, or referrals to different providers in hopes of securing coverage.

We're expected to screen and manage obesity in our patients (and document them in medical charts to comply with the BMI quality measure), but are not given any tools to help our patients succeed. It’s demoralizing to have most discussions end with, “Yes, your weight affects your health, but unfortunately, your insurance won’t cover the treatment you need.”

And now, with all the social media ads for GLP-1 medications, the situation is even more frustrating. Patients come in specifically asking about these weight loss drugs, but insurance companies label these visits as ‘not medically necessary.’ So not only can’t we offer the treatment they’re asking about, but they end up with an unexpected bill for the visit itself. It feels like we're letting our patients down at every turn, even though these barriers are completely outside our control.

End Rant

Unintended Impact on Patient Care

The BMI quality measure requires us to discuss weight every year, even when nothing has changed. This repeated ‘education’ can make our patients feel lectured to or judged. Worse, some may start skipping appointments or avoid seeking medical care altogether, even when they're sick, because they dread another conversation about their weight.

Cynefin Framework & Goodheart’s Law in Action

To quote from one of my prior articles: “The Quality of Quality Measurement:”

The challenge of simplifying complex medical decisions into clear metrics, combined with Goodhart's Law, creates a fundamental flaw in healthcare quality measurement.

The BMI quality measure took a complex socioeconomic & cultural issue squarely in the Cynefin complicated and complex domain and smushed it into the Clear/Simple domain. No wonder this measure achieved the following:

Better documentation in the medical chart as per Goodheart’s Law without any improvement in Obesity rates.

Increased burden on the PCP office to collect and submit data—allowing administrators to claim that they are providing good quality care (did I say I am cynical about quality measures?).

Now that we understand the problems associated with the BMI Quality Measure, let's discuss some tools and techniques that PCPs and ACOs can use to improve performance.

How can performance on BMI quality measures be improved?

There are two components to compliance:

Measure BMI

Document the plan if BMI is abnormal

BMI measurement is not an issue in most practices. The problem is reporting it to insurance companies. Let us look at how to “automate” reporting.

Automate Documentation Plan

Most EHRs can be set up to automatically populate standardized documentation like “patient counseled on healthy diet and exercise for weight management” during an Annual Physical. This can be achieved by “encounter plans” or “dotphrases” using functionality built into most EHRs.2

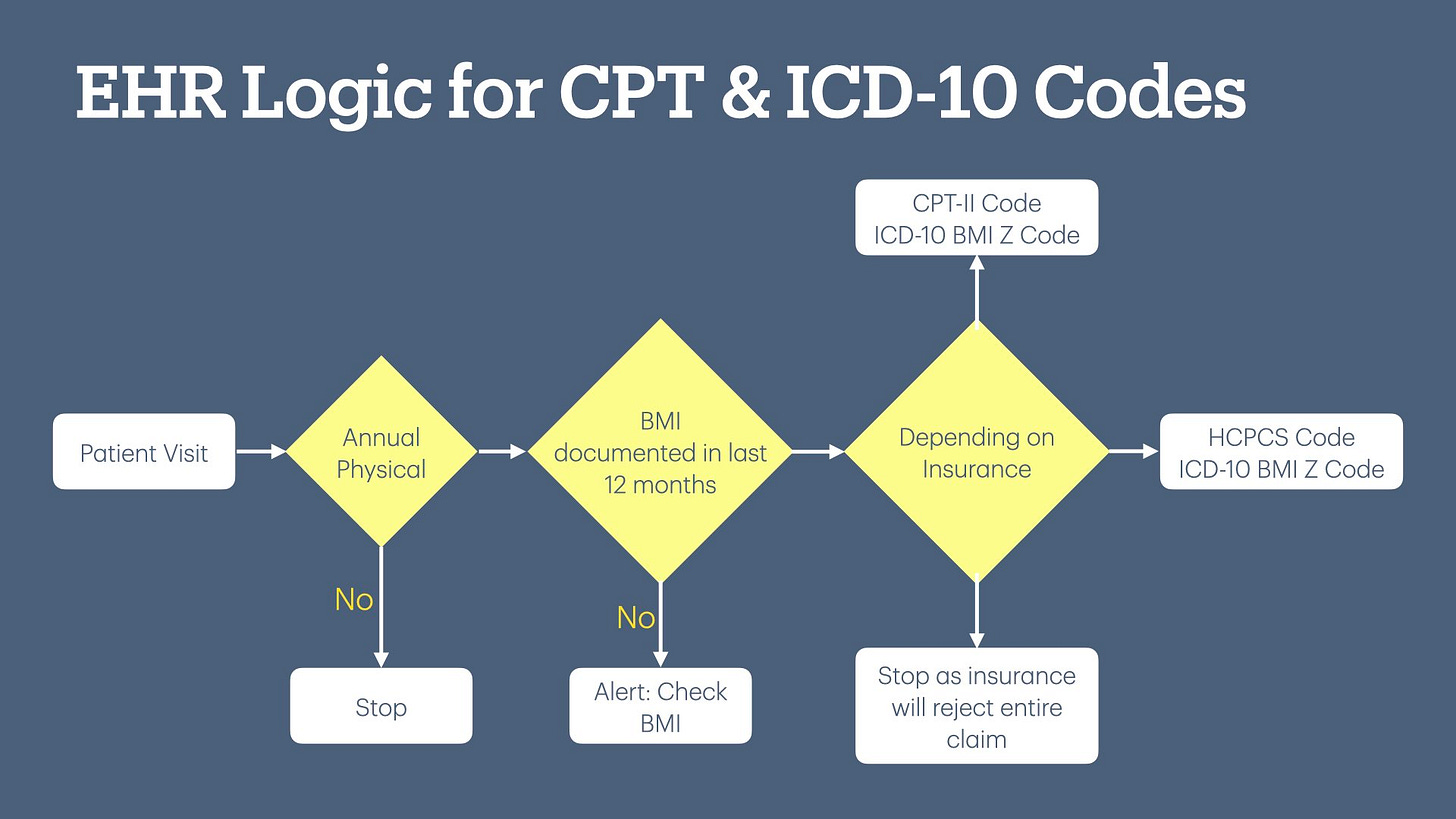

CPT-I and ICD-10 Codes

AMA defines several ICD-10 BMI Z-codes that are similar to the $0 CPT-II codes. (The Z-code list is in the attached PDF at the bottom of this article.) I discussed CPT-II codes in my last article, “The Devilish Details of Data Collection.”

The problem with these Z-codes is that most medical practitioners don’t know they exist, or how to use them correctly. There are two ways to solve this problem:

Use certified coders to bill the $0 BMI Z-code and ensure the entire bill is correct. However, this approach is expensive.

Develop functionality in the EHR to automatically add BMI Z-code to the bill based on documented BMI. This is an opportunity for improvement for most EHRs.

CPT-II Codes

Only one CPT-II code exists, and I don’t know how many insurance companies accept it.

3008F - Body mass index (BMI), documented

Automated workflow during an Annual Physical:

Drop CPT-II code 3008F with ICD-10 Z-code based on BMI. As far as I know, this has not been automated in most EHRs, and it is a development opportunity.

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Code

CMS defines a few HCPCS codes that function similarly to CPT-II codes, i.e., $0 codes to report quality. Like CPT-II codes, these codes indicate to CMS if the patient should be excluded from the denominator and, if included, if the doctor met the metric.

Table 3 in the PDF at the end of the article includes a list of these HCPCS codes.

Suggested workflow during an Annual Physical/Medicare Annual Wellness Visit:

Like CPT-I codes, the EHR system could be programmed to automatically drop HCPCS codes with the appropriate ICD-10 Z-code based on BMI.

Since different insurance plans accept different codes, to ensure compliance, I suggest that the EHR automatically drop all the necessary CPT-I, CPT-II, and HCPCS codes. However, this introduces the challenge of various intermediaries processing all these codes. I discussed this challenge in my previous article. To quote:

If the provider submits more than six CPT codes, there is no guarantee that these codes will reach the insurance company or will be processed to give credit for meeting the quality metric.

Artificial Intelligence Assisted Workflow

The EHR system can be enhanced with logic that selectively applies quality codes based on each patient's specific insurance provider. This reduces the chance of claim denial if certain insurances do not accept the CPT/HCPCS codes. Since this information is constantly changing and often hard to find, this scenario is a good use case for AI:

Use RAG AI to look up insurance policies to determine which health plan will accept which code.

Analyze successes and denials of past claims and modify the logic as appropriate.

Compare the submission of quality codes with reports from health plans to ensure that the PCP office received credit.

Supplemental Data Submission

Medical practices can submit BMI values via supplemental data to health plans using either EHR or data warehouse reporting functionality. The downside of this approach is that there is often no way to capture the “follow-up plan.”

However, this is still useful because a follow-up plan is not required for normal BMI. Submitting supplemental data ensures that the PCP office gets credit for reporting BMI screening for people with normal BMI—especially if the patient is not seen for an Annual Physical. It helps credit the PCP office for people with normal BMI (as long as the BMI was checked in the last 12 months).

For the follow-up plan part, doctors' notes containing the BMI screening follow-up plan need to be manually abstracted and submitted to the insurance company.

Electronic Clinical Quality Measure (eCQM)

CMS has an eCQM version of “BMI Measurement and Follow-Up” plan quality measure. Please see the CMS website for more details.

I am still delving into the details of eCQM, but the general philosophy seems to be:

Diagnosis: e.g., underweight, overweight, obesity, morbid obesity

Order: e.g., medication such as GLP-1 (good luck with insurance coverage), referral to a dietician, bariatric surgery, or some other order such as exercise referral that in your particular EHR uses the appropriate SNOMED code to satisfy the measure.

Summary & Downloads

I hope this article has convinced you of the useless nature of the BMI quality measure. I also hope you found the suggested strategies helpful in designing workflows and/or products to help PCP practices meet this useless quality measure.

Up Next

The next article will look at “Screening for Depression and Follow-Up Plan” quality measure. This quality measure tries to simplify nuanced clinical decision-making, potentially leading to overdiagnosis & overtreatment of people for depression.

Ogden, C. L. (2017). Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults, by Household Income and Education—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6650a1

Physicians should ensure that they are actually having a conversation about diet and exercise; otherwise, it is considered fraud.