From Doctors to Social Workers

How "Population Health" laid the foundation for Value Based Care

Welcome to PCP Lens. Please review the “About” page if you would like to learn more about me and this publication.

Our American Health System: Because who needs resources when you have good intentions?

Several changes in the last few decades have resulted in the decline of primary care. In this newsletter, I will try to unpack what happened, what is happening, and how current market dynamics and policies are reshaping healthcare, especially primary care.

This is the first article in a series to lay the foundation of value-based care to understand healthcare’s current landscape and how it affects primary care.

What better way to start this newsletter than by understanding “Health” and its construct, “Population Health.”

The video version of this article is embedded below and on my YouTube Channel.

Audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

What is “Health”

The best definition of health comes from the World Health Organization (WHO):

A state of complete mental, physical, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

According to the WHO, the determinants of health (i.e., factors that make people healthy or ill) include:

Social and economic environment

Physical environment, and

The person’s individual characteristics and behaviors

The 3rd determinant is heavily influenced by 1 & 2. We tend to focus on individual risk factors while ignoring social, economic, and environmental determinants.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has another good quotation regarding health determinants:

Health begins where you live, work, and play.

What is conspicuous by its absence is the mention of “doctors” and “medical treatment” in the definition of health or the determinants of health.

The Medical System and Health

Several versions of the image below on the internet claim “medical care” as being responsible for 20% of a person’s health. They all seem derived from a single source: “Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Going Beyond Clinical Walls: Solving Complex Problems” (October 2014). I have not been able to access their website and the article to determine how they arrived at the 20% number.

The medical system is good at:

Treating acute illness

Treating chronic disease to decrease its progression and development of complications

Screening for chronic diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and cancer

Education about risk factors to hopefully affect change

Let me restate my previous comment about health determinants: socioeconomic and environmental factors heavily influence individual risk factors.

Socioeconomic and environmental factors heavily influence individual risk factors.

From a “Health” standpoint, the medical system can attempt to affect individual risk factors but has no control over socioeconomic and environmental determinants that may be responsible for these risk factors. Changing individual risk factors without changing socio-economic and environmental factors is hard.

Aside: The Role of Annual Physicals in Health:

You may wonder about the Annual Physical’s role in keeping people healthy.

Plenty of data support the value of an Annual Physical in educating people about healthy habits. The patient exam, labs, and other testing have little value for people without risk factors.1 The lack of data that an Annual Physical improves the health of an individual creates an interesting problem:

Health-conscious people, who are generally better educated and healthier with fewer risk factors (e.g., smoking), are more likely to get an Annual Physical. These people are the least in need of health education.

People in lower socio-economic groups often lack access to Annual Physicals due to financial constraints (e.g., insurance coverage, lack of transportation, or inability to afford to take time off work) or limited education—these people would benefit more from health education.

However, as mentioned earlier, socio-economic and environmental determinants heavily influence individual choices that increase the risk for disease. In this case, educating people is generally not enough to affect change.

The medical profession’s role in this scenario is to recognize the risk factors and monitor and start treatment early when they manifest as an illness (e.g., smoking causing COPD or lung cancer).

The final issue with the Annual Physical is that Primary Care Providers are so overburdened that they don’t have time to educate and rely more on patient exams and testing. This focus on physical exams and labs removes the primary benefit of an Annual Physical.

For those of you wondering about the role of cancer screening in healthcare, the science is not as settled as you think.2

Now that we understand the difference between health and illness/disease, let’s move on to Population Health.

Population Health

The earliest reference to Population Health was in a book published in 1994 by Canadian authors Evans, Barer, and Marmor: Why Are Some People Healthy and Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations.

In the book, the authors loosely defined Population Health as:

The study of why a certain population is healthier than others, determine risk factors leading to poor health and implement policies to mitigate and improve health.

The original intention of Population Health was to study why a population is healthier or sicker than others. Researchers and policymakers would use this data to suggest policy interventions to modify health determinants to improve the population’s health.

Here is an example (simplified for illustration):

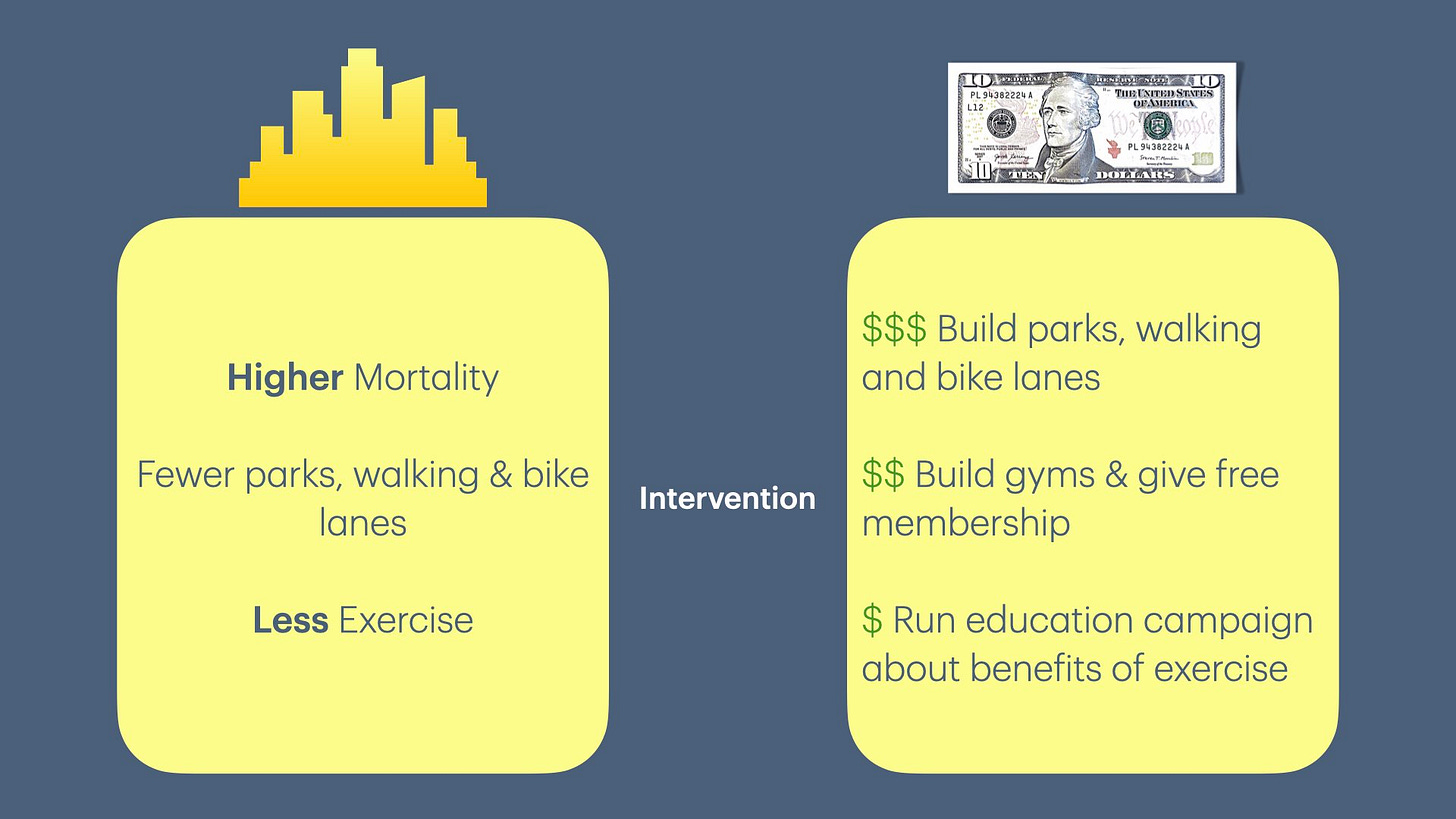

Population 1 has higher mortality than Population 2, which lives in a different geographic area.

Population 2 has more parks, walking, and bike lanes than Population 1.

In this case, the health determinant is “more physical activity” due to access to parks, walking & bike lanes.

The government changes regulations and/or zoning codes in the geographic area where Population 1 resides to encourage the construction of parks, walking paths, and bike lanes.

Population 1 starts getting more exercise as they have access to parks and lanes.

Over time (generally measured in decades), mortality rates between the two populations become equal (assuming there is no other difference).

In the United States, when we imported the term “Population Health,” it evolved from a research/public policy framework to an economic framework.

David Kindig, in 1997, was the first person to use the economic framework to redefine “Population Health” in his book Purchasing Population Health:

“the aggregate health outcome of health-adjusted life expectancy (quantity and quality) of a group of individuals, in an economic framework that balances the relative marginal returns from the multiple determinants of health.”

In practice, this translates to—resources are limited, so we must allocate them effectively. This economic framework model lets decision-makers decide which health determinants to allocate resources to maximize value (or ration care).

Let’s continue with our previous examples of Population 1 having higher mortality. A study of health determinants in the two populations may lead to 3 choices that decrease mortality in Population 1 and their cost/benefit analysis:

Build parks, walking and bike lanes—very expensive, with the most benefit.

Build gyms and give free membership—moderately expensive, with some benefits.

Run an ad campaign to educate people about the benefits of exercise—the least expensive with minimal benefit.

We can all agree that building parks, walking, and bike lanes will provide the most benefit in the long term. However, due to a limited budget, gyms with free membership may be the only viable option! And this is also how we ration care, where the disadvantaged population ends up sicker than people of higher socio-economic status.

However, in America, when there is a bad outcome, we have to be able to blame someone. It is harder to blame when a large population is involved. So, we have to reduce the number of people in the measured group and find someone responsible for caring for that group.

In 2003, Kindig and Stoddart simplified the definition of “Population Health” as:

"the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group."

The authors justified this simplification by the need to return to the original Canadian roots to capture healthcare determinants and apply the definition to medical care.

Replacing the word “population” to a “group of individuals” in the definition had two impacts on healthcare, as the authors intended:

This allowed the principles of Population Health from its original definition to be applied to a much smaller group of individuals (e.g., PCP panel)

Link a single health outcome (e.g., increased mortality) to its health determinant (e.g., lack of exercise).

From a medical perspective, this makes it easier to define targets (a.k.a. quality and cost), set the target, measure, and hold the medical profession, i.e., PCPs, accountable. Furthermore, the change in this definition made medical professionals responsible for Population Health interventions instead of the government.

Quick PCP Rant:

From a PCP perspective, this translates to—“You are not doing enough to educate your patients about exercise, which is why your patients have a higher mortality.”

Reading the above statement makes you realize how ridiculous the statement is. Primary care physicians have no control over individual behavior in making them exercise.

Furthermore, from a socio-economic & environmental standpoint, individuals may be unable to exercise, which PCPs don’t have any control over (e.g., lack of parks, gyms, financial difficulties to afford exercise equipment or gym membership, lack of time as working two jobs to make ends meet).

(I chose a simplified example to illustrate my point without going into detailed medical nuances.)

End Rant.

Triple Aim and Population Health Management

In 2008, the Institute of Healthcare Improvement published a seminal article in Health Affairs defining the Triple Aim to improve the US healthcare system. The Triple Aim includes:

Improving the health of populations, a.k.a. Population Health

Improving the experience of care

Reducing per capita costs of healthcare

This article not only enhanced the awareness about “Population Health” but also introduced the concept of Population Health Management.

Under Population Health Management, the medical system would need to allocate resources appropriately toward health determinants that directly correlate with improved health outcomes and reduced costs in a clinical setting, i.e., the medical system would be responsible for Social Determinants of Health (SDOH).

What about Public Health?

According to the CDC Foundation (emphasis mine):

Public Health is the science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities. This work is achieved by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing, and responding to infectious diseases. Overall, Public Health is concerned with protecting the health of entire populations. These populations can be as small as a local neighborhood or as big as an entire country or region of the world.

Even though the definitions of Public and Population Health are very similar, Public Health is now confined to a much more narrow set of activities carried out by the government and public health workers.

Population Health has taken over the original meaning of “Public Health.” The private sector is now responsible for what was originally the government domain—promoting and protecting the health of people!

Continuing with our Population 1 example, the government can build parks, walking, and bike lanes, which create social conditions conducive to exercise and decrease mortality.3 Health plans may provide free gym membership, which a few people may use. PCPs can educate people about the benefits of exercise but have no other control (but are held accountable for health outcomes).

When the entity (government, insurance, PCP) responsible for health outcomes changes, the interventions that the new entity can or will implement will change depending on the resources available. If, as a country, we decide not to pay for socio-economic & environmental health determinants (building infrastructure and providing services), this will lead to poor outcomes. Transferring this responsibility to insurance plans or PCPs limits the intervention choices, and these choices are generally a lot less effective.

As a country, we have decided not to pay for socio-economic and environmental health determinants.

We transferred this responsibility to the profit-making medical-industrial complex.

Since the medical-industrial-insurance complex needed a scapegoat, they made primary care responsible for these Social Determinants of Health (SDOH). This redefined the role of primary care and set in motion the process of turning doctors into social workers.

Up Next?

This article lays out how Population Health laid the foundation for transitioning the responsibility of managing Social Determinants of Health from a function of the government to your PCP.

In the next newsletter, we will discuss how these frameworks led to the evolution of Value-Based Care, the contracts that force your local PCP office to manage the “Social Determinants of Health (SDOH).”

If you liked this article, please consider sharing it.

Liss, D. T., Uchida, T., Wilkes, C. L., Radakrishnan, A., & Linder, J. A. (2021). General Health Checks in Adult Primary Care: A Review. JAMA, 325(22), 2294–2306. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6524

Prochazka, A. V., Lundahl, K., Pearson, W., Oboler, S. K., & Anderson, R. J. (2005). Support of Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Annual Physical Examination: A Survey of Primary Care Providers. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(12), 1347–1352. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.12.1347

Bastian, H. (2014, March 23). The Disease Prevention Illusion: A Tragedy in 5 Parts. Absolutely Maybe. https://absolutelymaybe.plos.org/2014/03/23/the-disease-prevention-illusion-a-tragedy-in-5-parts/

Bretthauer, M., Wieszczy, P., Løberg, M., Kaminski, M. F., Werner, T. F., Helsingen, L. M., Mori, Y., Holme, Ø., Adami, H.-O., & Kalager, M. (2023). Estimated Lifetime Gained With Cancer Screening Tests: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Internal Medicine, 183(11), 1196–1203. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.3798

Prasad, V., Lenzer, J., & Newman, D. H. (2016). Why cancer screening has never been shown to “save lives”—And what we can do about it. BMJ, 352, h6080. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6080

Young, D. R., Cradock, A. L., Eyler, A. A., Fenton, M., Pedroso, M., Sallis, J. F., Whitsel, L. P., & On behalf of the American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. (2020). Creating Built Environments That Expand Active Transportation and Active Living Across the United States: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 142(11), e167–e183. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000878

Sudeep- This is so informative. Especially the chart on health determinants. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 40% is due to socio-economic factors. And perhaps surprisingly, only 10% is physical. I appreciate you sharing this.