This is the last article in the Foundations of Value-Based Care (VBC) series. However, since VBC appears to be the way of the future for health payments, I will continue to discuss its impact in future articles. If you have not read the previous articles on Population Health, Value-Based Care, Patient Attribution, and Risk Adjustment, I strongly encourage you to do so.

There Are Only Two Ways To Make Money: Bundling and Unbundling.

Jim Barksdale, CEO of Netscape

In this article, we will discuss bundled payments. Since many articles are already touting the benefits of bundled payments, I will focus on their negative aspects.

For readers looking for a more in-depth yet easy-to-read analysis, I recommend this article by the American Hospital Association (PDF link): Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiatives: Considerations for Providers.

The video version of this article is embedded below and on my YouTube Channel.

Audio podcast and Video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

What is a Bundle?

A bundled payment is a fixed-price agreement for a predefined episode of care and all related services or all care for a medical condition.1

Let’s deconstruct this definition and consider some of the nuances:

A Predefined Episode of Care:

To define an episode of care, we need to consider the following:

The medical problem (e.g., hip arthritis) with the proposed treatment plan (e.g., hip replacement).

What constitutes an episode: i.e., the time during which care is rendered.

Defining the time period during which an episode occurs can be challenging. Let’s take two examples:

Hip replacement for hip arthritis:

When does this episode start? The bundle could begin on the day of the orthopedic physician’s office visit during which a decision is made for surgery, the day of hospitalization, or the day of surgery (which may differ from the day of hospitalization).

When does the episode end? The bundle could end on the day of hospital discharge or at a specified time after discharge (e.g., one month after discharge).

Diabetes Management:

When does the episode start? At the onset of diagnosis, or on Jan 1 of every year.

When does the episode end? When the patient dies, or Dec 31 of every year.

“All care” for a medical condition

There are again two components:

What medical care is part of the “predefined episode?”

Is physical therapy after hip replacement part of the “all care?”

Is a primary care visit for hip pain part of the “all care” because the person did not receive a call back from their orthopedic office?

If a person slips and falls after hip replacement while trying to get groceries and breaks their hip implant, is it part of the predefined episode?

If the person slips and falls while doing physical therapy as part of recovery, is it part of a predefined episode?

Which medical professionals is “all care” applied to?

Only medical professionals working within the same Tax ID Number (TIN), E.g., hospital and employed physicians.

All medical professionals involved in care, even if they belong to different TINs: E.g., An independent orthopedic surgeon performs surgery at an affiliated hospital, and then the patient does physical therapy using a private company that is closer to their home, i.e., three different TINs. (The challenge here is—who negotiates the bundle, receives and distributes payments).

Fixed Price Agreement

Once a bundle is defined, then it needs to be priced. While pricing a bundle is an actuarial art in itself, here are the general rules:

The average cost of all the individual services that are part of the bundle

The Total cost of this average.

Adjust for the geographical wage/price threshold (e.g., labor is more expensive in some areas than others).

Risk adjustment for the complexity of patients in the bundle.

In this formula:

BPPrepresents the Bundled Payment Price,Cirepresents the cost of individual servicei,nis the total number of services in the bundle,GAFis the Geographic Adjustment Factor, andRAFis the risk adjustment factor for patient complexity.

Before considering some of the problems with bundled payments, let's take a quick look at its history and current state.

CMS and Bundled Payments

In 1983, CMS, which administers Medicare, introduced the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) as a bundle to pay hospitals. Instead of paying hospitals a la carte, Medicare classified hospital cases into 500 groups with the expectation that patients within each group would need similar resources (e.g., all patients admitted with pneumonia would, in theory, need similar services). Under the DRG system, hospitals were paid a flat rate per case for inpatient hospital care, with the expectation and incentive that hospitals would control the cost of hospitalization (and there is some data to support that DRG implementation was a successful policy).

In 1991, CMS experimented with a CABG bundle that included hospital and physician services, but then abandoned it. I have not found any information on why CMS abandoned the CABG bundle—my suspicion is that it was due to hospitals and surgeons being in different TINs—but more on that below).

Since then, CMS has experimented and continues to experiment with several different bundles, the most recent being the BPCI Advanced Model, which is ongoing. However, there is mixed evidence of whether CMS saved any money from any of these newer bundles, especially when you account for the complexity of administering the bundle (the exception being hospital DRG—which has also been gamified using case-mix index and other tools.

Private Insurance Companies and Bundled Payments

Private insurance companies, especially Medicare Advantage, have followed CMS's footsteps in creating bundles. Most of these bundles are for surgical procedures, such as hip and knee replacement, but some insurances also have bundles for pregnancy care.

Mini-Bundles

Health plans also have what I am going to call mini-bundles. The best example of this is the removal of sutures. This mini-bundle bundles the insertion and removal of sutures in a single payment. For example, suppose you went to the emergency room for a laceration, and they stitched you up. In this case, most plans will not cover the cost of your primary care visit to remove those sutures. This is generally not a problem when the ER and the PCP are part of the same health system, i.e., the same TIN. This, however, becomes a problem for independent PCPs as they do not get reimbursed for suture removal—some PCPs try to get around this by using a different diagnostic code. In contrast, others will redirect you to Urgent Care.

A Bundle of Problems

Blurry Bundle Boundaries

While the bundle for a surgical procedure is more easily defined, it becomes more challenging with chronic diseases.

Let us try to define a care bundle for diabetes using the parameters discussed above:

Predefined Episode of care

Time period: 1 year, from Jan 1st to Dec 31st

“All Care” for Diabetes:

What medical care is part of the “predefined episode?”

Diabetes-related office visits, urgent care, and hospitalization—how do you differentiate between an office visit for diabetes vs a more comprehensive visit in which multiple medical problems are addressed in the same visit (which is most of primary care)

Labs ordered for diabetes—easily gamified by ordering the same labs under a different diagnosis

Diabetes medications—can be gamified as some medications can be used for different medical problems. E.g., Lisinopril is used both for hypertension and diabetic nephropathy.

Which medical professionals is “all care” applied to?

Endocrinology: prescribing most diabetes medications

Primary care: prescribing Lisinopril for diabetes kidney protection and gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy

Podiatry: Diabetic foot disease

Ophthalmology: Diabetic eye disease

Fixed price agreement

Easily gamed using Risk Adjustment

As you can see, this gets very complicated quickly and opens up the system to gamification and consolidation (we will examine the hip replacement bundle later in this article).

Risk Adjustment and Case-Mix Index

Remember the equation from above—the payment in a bundle is dependent on the risk adjustment (outpatient setting) or case-mix index (inpatient setting). Making the patient look sicker, a.k.a. coding the appropriate level of risk, is an easy way to increase payments.

Unbundling the Bundle

This involves removing reimbursable codes that would generally be part of the bundle. There are several ways to do it, but I am aware of 2 common methods that are used:

Provide the same treatment under a different ICD-10 disease code: For example, prescribe Lisinopril under the hypertension ICD-10 code instead of Diabetes with nephropathy.

Claim “Pre-existing disease” and make the argument that it should not be part of the bundle: Why do you think most people get a urine analysis when admitted to the hospital? If the urine on admission is “dirty” or shows bacteria, the hospital can claim a higher DRG as there is a “pre-existing condition of urinary tract infection.”

Most urine samples collected in ERs are dirty due to collection technique or asymptomatic bacteriuria that does not need treatment.

Broken Bundles—When Patients Move or Switch Plans

What happens when a patient switches either providers or insurance plans that are not part of the bundle? This can happen in 3 ways:

The patient moves to another city or State and establishes care with new providers who are part of the same bundle while keeping the same insurance. E.g., large national employer plan where the employee was transferred to a different location.

How is the bundled payment split between the providers in the different cities/States?

The patient keeps the same providers but changes insurance plans.

How will the insurance reimburse the provider for the care that was already rendered, especially if the insurance pays out once a year or at the end of the bundle?

My wife and I were caught in this exact scenario as we were in a pregnancy care bundle and switched insurance plans. The insurance refused to pay the obstetrician, and the OB office transferred the entire bill, amounting to several thousand dollars, to us. After several calls to the OB office and insurance company, I finally figured out that the insurance company was refusing to pay the OB office as the pregnancy care cycle was not complete! After much back and forth with me explaining how bundled payments work to the insurance agents, I was able to resolve the issue.

The patient switches both insurance plans and providers.

In this case, the provider may be left fighting the insurance for reimbursement, which, if denied, will be a much higher amount than if it was for an individual service.

Bundling Providers to Make a Bundle on Profits

A bundled payment is easier to administer when all the healthcare entities are under the same TIN so that reimbursement is sent to one place. However, when different healthcare entities under different TINs are involved, then who receives the payment, and how will it be distributed to all the involved parties?

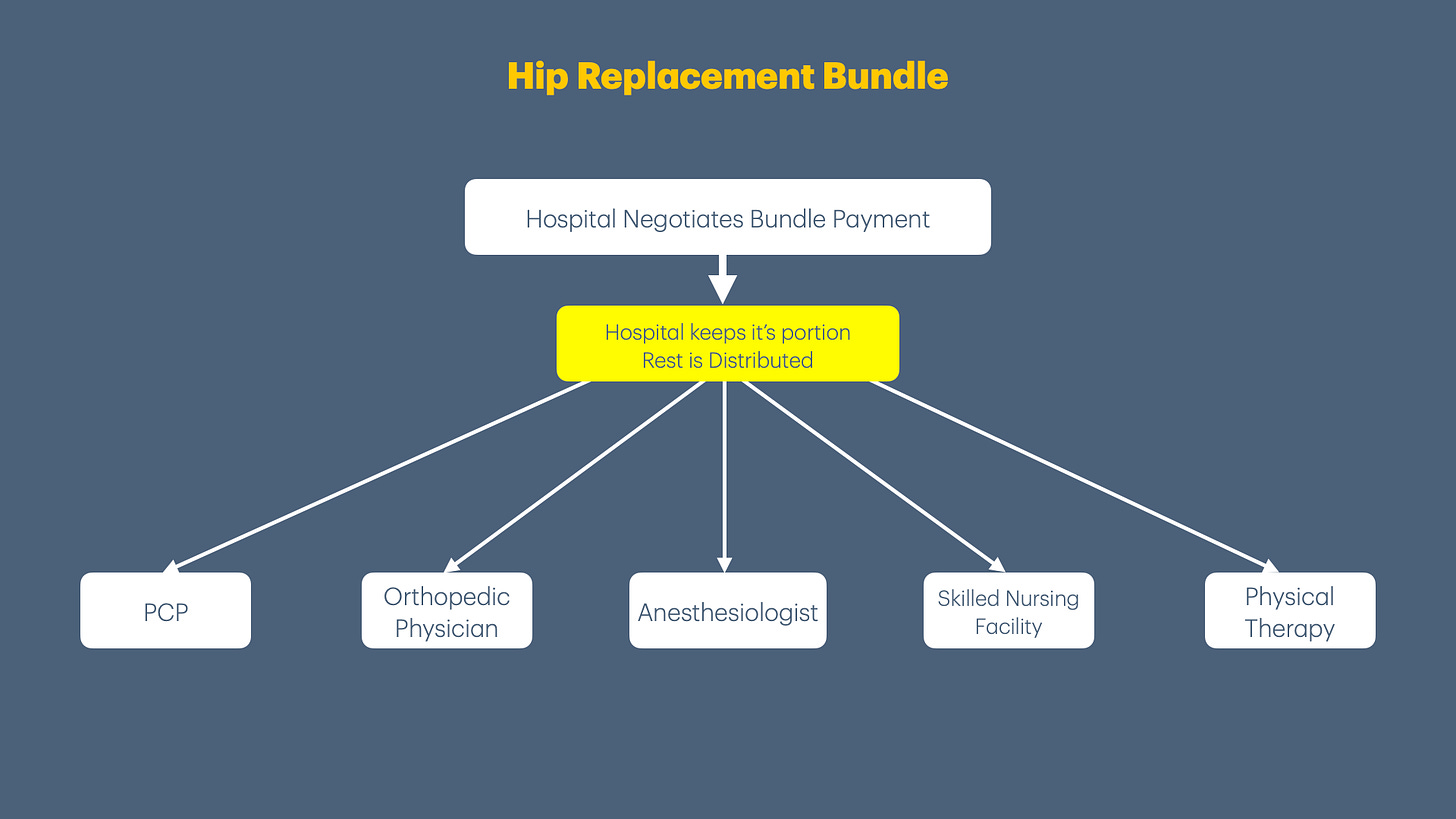

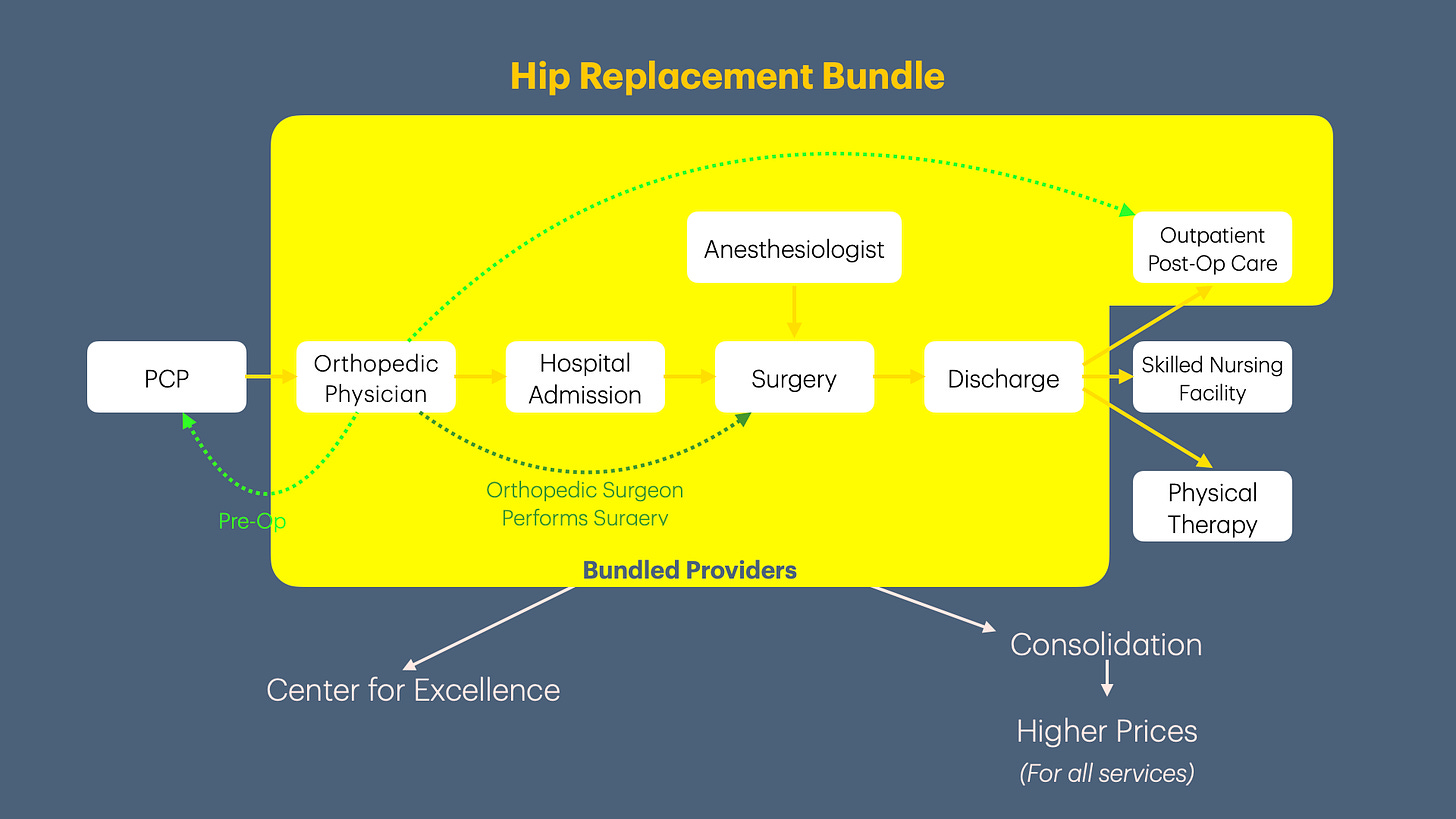

For example, in a hip replacement bundle, several healthcare entities may be involved. These entities include an orthopedic surgeon, anesthesiologist, primary care physician, hospital with employed staff (e.g., nurses), skilled nursing facility (SNF), and outpatient physical therapists.

If the hospital (the largest entity in this value chain) negotiates the bundled payment, then all the other healthcare entities that provide medical services as part of the bundle, will take a cut out of the hospital’s profit margin. Also, if an adverse event occurs during the bundle episode leading to higher total costs, then who bears this cost?

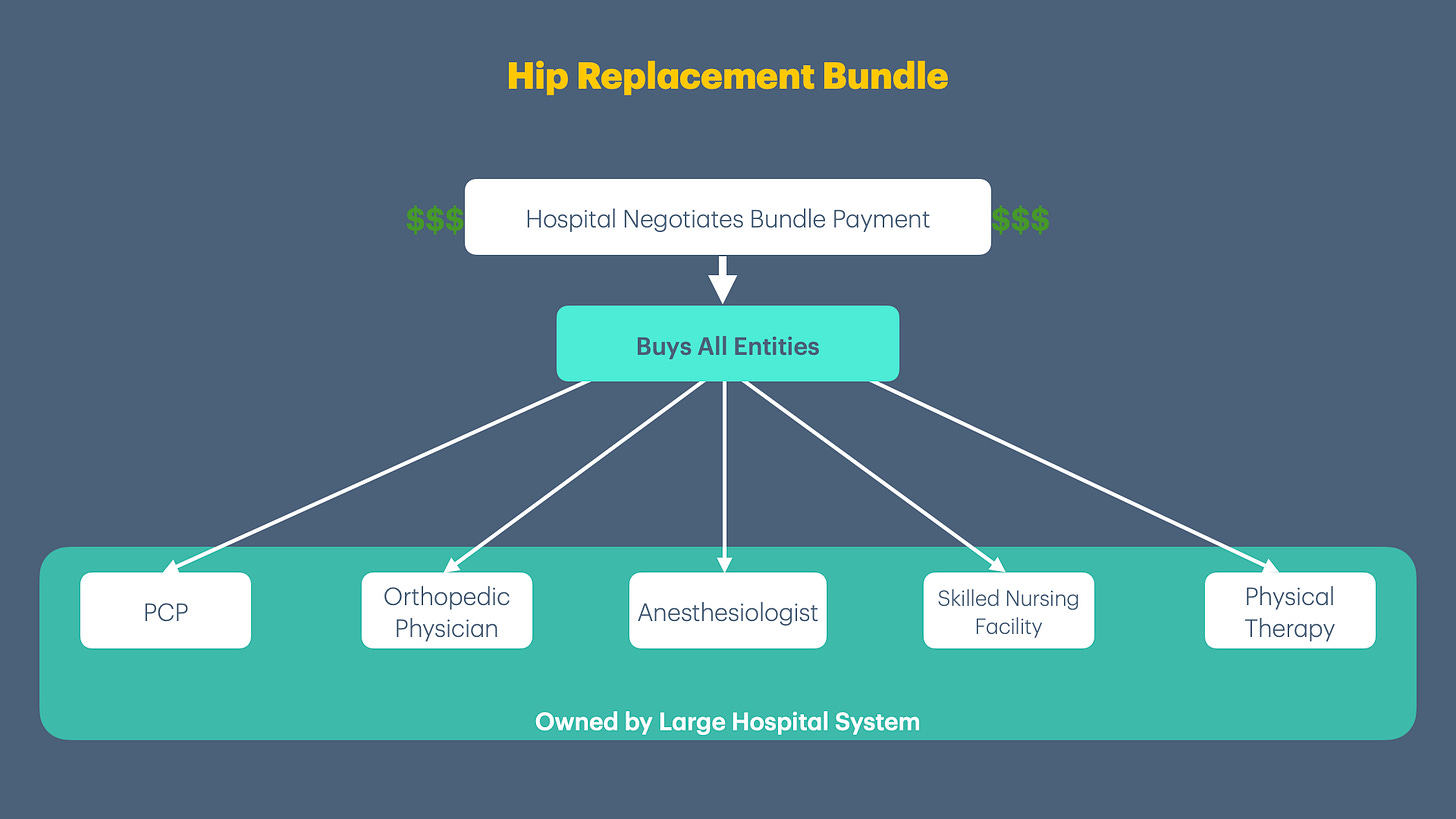

From the large health systems perspective, especially if they are contracting with the insurance company, it would be easier to buy these providers and keep all profits in-house instead of sharing downstream bundle payments with other providers.

Therefore, bundled payments, intended to create centers of excellence, may instead result in healthcare consolidation. These consolidated entities then can go back to the health plan and negotiate higher prices for the bundle, negating any savings.

Untangling Overlapping Bundles

Let us take the example of 2 groups of health entities, each with its own negotiated bundled payment (with different reimbursement rates):

Hospital with operating room facility, nurses, and technicians.

Accountable Care Organization (ACO) with independent providers such as orthopedic physicians, anesthesiologists, primary care, and physical therapists.

If a patient needs surgery at the hospital, this can create problems if the surgeons, anesthesiologist, and primary care physician are part of the ACO:

Which bundle rate is used for payment (hospital negotiated rate or ACO negotiated rate)?

Which entity receives the bundled payment: the hospital system or ACO?

This can get complicated quickly if there are multiple health entities, each with its own negotiated bundle. The easiest way out of this is to own all the entities under one umbrella, i.e., to consolidate.

VBC Foundation Series Summary

The Value-Based Care (VBC) foundation series shows how VBC has dramatically increased administrative complexity. Small practices don’t have the resources to manage this complexity, which forces them to exit healthcare via consolidation or bankruptcy. Larger organizations are able to manage the complexity inherent in VBC contracts and increase their moat. This prevents new medical practices (especially small practices) from entering the marketplace, reducing competition and solidifying the incumbents’ market position. This slowly trends towards monopolies or oligopolies. These firms concentrate enough power to capture regulators and influence laws that allow them to maintain their power, or escape consequences for not providing high-quality healthcare.

Up Next

In the next few articles, we will look at Quality Metrics. We will delve into the details of how health plans, under the guise of improving quality, bury medical practices under a mountain of data collection requirements to maintain their profit margins.

If you liked this article, please consider sharing it.

You can unlock access to the paid membership tier for free using the link below to share this article via email, text message, or social media. Learn more about these perks and track your progress on the leaderboard.